How Neuroscience Can Empower (and Inspire) Marketing

In 1957, Advertising Age created mass-hysteria across the nation when it published the results of a scientific study on subliminal advertising. The study, conducted by market researcher James Vicary, showed how flashing instructions on a movie screen for just 1/3,000th of a second (Drink Coca-Cola! Eat Popcorn!) caused snack bar sales to skyrocket. The article claimed to have tested more than 45,000 viewers over a period of six weeks, during which Coca-Cola sales in the test theater spiked 18 percent and popcorn 57.5 percent. As a result, the country went nuts. Congress and the CIA both investigated and everyone called for the technique to be banned, fearing that if it could be used to sell soft drinks it could also be used to spread Communism and immorality.

In 1957, Advertising Age created mass-hysteria across the nation when it published the results of a scientific study on subliminal advertising. The study, conducted by market researcher James Vicary, showed how flashing instructions on a movie screen for just 1/3,000th of a second (Drink Coca-Cola! Eat Popcorn!) caused snack bar sales to skyrocket. The article claimed to have tested more than 45,000 viewers over a period of six weeks, during which Coca-Cola sales in the test theater spiked 18 percent and popcorn 57.5 percent. As a result, the country went nuts. Congress and the CIA both investigated and everyone called for the technique to be banned, fearing that if it could be used to sell soft drinks it could also be used to spread Communism and immorality.

Within a year, the study was revealed to have been a hoax. But that didn’t remove it from the public consciousness and for decades after people believed that our movies, TV and magazines were peppered with secret messages and images of sex in ice-cubes. (I remember feeling particularly disappointed with myself in high school when I was unable verify that last claim.)

But hoax or not, while our ads may not be subliminal, the part of our brain that actually makes our buying decisions is. That’s the story in Doug Van Praet’s fascinating book, Unconscious Branding, How Neuroscience Can Empower (and Inspire) Marketing. “Consumers are not in control of their brand choices,” he writes. “Humans operate from two separate and often contentious cognitive systems and the mind that drives most of our behavior is ironically the one unbeknownst to ourselves.” Van Praet cites numerous studies showing that 95% of our thinking and most of our choosing occurs in our unconscious minds.

“As consumers,” he continues, “we make choices without understanding their foundations, and as marketers, we sell and brand products without understanding how to truly connect them to people. We are all playing a game, and we don’t even know how that game is being played.”

And yet there is a growing body of work in neuroscience and cognitive science that can help us understand the game and use it to serve our customers better. Van Praet cites work done by the Max Planck Institute where researchers viewing brain scans were able to predict participants’ decisions about seven seconds before they consciously made their choice. Of course, it’s one thing to do that if you have a fMRI machine at your disposal. But how do you put this science to work if you don’t have access to brain scans?

“The question remains,” Van Praet points out. “If an animal can be preprogrammed to react to a specific environmental feature, can humans be preprogrammed in a similar fashion? For instance, is it possible that humans respond to certain essential features in marketing? And can we reject an advertisement that violates these rules or accept one that recognizes and leverages them? Are there unconscious triggers that both marketers and consumers are unaware of? And, if so, what are they and how can they be recognized and utilized to create stronger bonds with brands? Can we begin to recognize the presence of evolved psychological mechanisms in our marketing programs, such as the coalition formation and territoriality of brand clubs and loyalty programs, or the predator avoidance phenomenon of angry bloggers who warn their digital tribes of the perilous deception of unscrupulous marketers?”

As it turns out, the answer is yes, we can. Among the cognitive scientists Van Praet cites are two of the founders of the field of evolutionary psychology, Leda Comides and John Tooby from the University of California, Santa Barbara. Their work is about “the recognition that the human brain consists of a large collection of functionally specialized computational devices that evolved to solve the adaptive problems regularly encountered by our hunter-gatherer ancestors. Because humans share a universally evolved architecture, all ordinary individuals reliably develop a distinctively human set of preferences, motives and specialized interpretation systems–programs that operate beneath the surface of expressed cultural variability, and whose designs constitute a precise definition of human nature.” In other words, our minds are like smartphones preloaded with hundreds, even thousands of apps that all run in the background simultaneously, without us even knowing. And we all have very similar apps that work in very similar ways. If you know what apps your customer base is running, you can interact with them on a very sophisticated level.

“To ignore these universal mental programs,” Van Praet says, “is to overlook some of the most fundamental ways to understand and change behavior, because we all share a common ancestry.” Astonishingly, he relates, the genetic record shows that we are all descended from a small population of about 600 breeding individuals. So, yes, we may all be unique and wonderful individuals, but apparently we’re not all that unique.

But that doesn’t mean our choices are made for us or that we can’t change our minds about brands we’re attached to. You can change from Coke to Pepsi any time you want. But if you make that change, it’s likely that your decision is triggered by a subconscious memory of a previous event or association with the brand. Maybe you were on a rooftop bar in Manhattan and saw the vintage neon Pepsi sign across the East River. Or maybe you saw someone drink it in a movie. After all, who doesn’t want to be like Brad Pitt?

So how can we use this knowledge to improve the way we communicate, not just in marketing but in all the ways we work to engage and enroll others? Van Praet gives seven steps for changing consumer behaviors (and, by the way, I think these are just as important as leadership steps to build a culture and engage your people in a shared passion for your organization’s brand).

Step One—Interrupt the Pattern

Our minds work through processes of pattern recognition. If we want to shift someone’s beliefs and behaviors, we have to interrupt their perceptual patterns by doing something interesting and different.

One way to interrupt the pattern is to surprise people in emotionally meaningful ways. Van Praet was at ad agency Deutsch LA when they created an spot then went on to be voted the greatest TV commercial of all time, the 2012 Volkswagen Passat ad where a pint-sized Darth Vader tries unsuccessfully to use “the Force” until his dad secretly starts the car engine with a button on his key fob. It didn’t matter whether or not remote starting was a feature all America was waiting for; what mattered was that the little story was different enough to capture our attention and instantly create an emotional bond … with the VW brand.

Step Two—Create Comfort

Because we don’t like change, we tend to gravitate to the familiar. We rely on predictable patterns so, even though we may be interested in what is different, we need it to feel safe and trusted before we can engage.

Laughter creates comfort as does a focus on reducing frustration. Whatever a brand does, it needs to be consistent. Have you noticed that while Southwest Airlines ads may change over the years, the campaign itself always looks the same and is comfortingly tongue in cheek, even though their product—air travel—is inherently uncomfortable and anxious? They’re making you comfortable by the way they market.

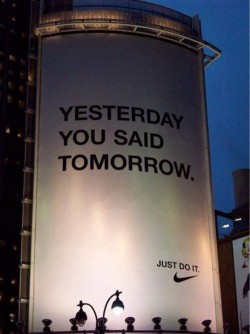

Step Three—Lead the Imagination

Our prefrontal cortex gives us the unique ability to plan behavior and create new possibilities. It works like an alternate reality simulator by letting us imagine the benefits of a better life and anticipate the consequences of our actions.

Our prefrontal cortex gives us the unique ability to plan behavior and create new possibilities. It works like an alternate reality simulator by letting us imagine the benefits of a better life and anticipate the consequences of our actions.

One way to do that is to promise a better life, not just a better product. This Nike billboard is one of my favorite ads of all time, just black type on a white background: “Yesterday you said tomorrow. Just do it.” We don’t just buy shoes from Nike, we buy access to our goals and dreams.

Step Four—Shift the Feeling

We do what we do because of how we feel. We give things value through our emotions. And because of the way our brains are wired, emotions influence our thinking more than our thinking influences our emotions.

Van Praet remembers the day he bought his current iPhone. The salesperson in the Apple Store handed him the box and said, “Do the honors.” By turning the opening of the box into a ritual, the salesperson took the experience out of the ordinary and cemented it in mythical importance. Guinness does something similar when they show the correct way to pour a bottle of Guinness into a glass. They make it a ceremonial act, not an ordinary one.

Step Five—Satisfy the Critical Mind

Don’t underestimate the value of the conscious mind: it gives us the exclusive ability to rationally reject an idea that doesn’t make sense based on our experience and emotions. Often, in order to act, we need to logical permission from our mind.

Did you know that Lexus cars have gold plated airbag connectors? That’s not unique to their brand—lots of cars have them for better connectivity in the critical moment—but by advertising that theirs had them, they communicated both the emotion of luxury and the rationale of safety.

Step Six—Change the Associations

Our minds and memories work by association. Repetition and emotion strengthen these neural associations so that they become fixed and automatic. If we want to change the perception of anything, we have to change our associations.

When shoppers looked at the meat counter in 1987, they were beginning to shy away from red meats and fatty pork. But when the National Pork Board began a campaign for “The Other White Meat,” pork sales soared. Suddenly, pork joined the ranks of healthier poultry because it shared a single common trait: it turns white when you cook it.

Step Seven—Take Action

Our brains exist for movement. Things that don’t move don’t have brains. Since physical actions use more of our brain than just imagining an experience or a behavior, they have a powerful effect on our associations. This locks in the experience.

Red Bull doesn’t just make energy drinks, they make energy sports events, like their Formula 1 racing team which has taken the world championship the last four years in a row. By linking their brand to high performance thrills, they create an action connection that is highly motivating to their brand fans. And if you’ve travelled to a race that has Red Bull branding all over it, bought the t-shirt and cheered on the team, you’ve made your brand fandom into an odyssey.

So that’s all great, but what don’t the same old fears that surrounded subliminal advertising come up? Can’t all this neuroscience be used to promote Communism or that other political party you hate so much? Van Praet says no, not really.

“It’s been said there are only two ways to win: beat the competition or achieve your own goal. If you are driven by a desire for the former, you will be hijacked by your genes’ basic programs, wired to succeed in environments that have little relevance in today’s world. And you will not be alone. Much of the business world continues to operate in the mind that reinforces fear and aggression, the physical, reptilian unthinking brain that seeks domination over others. What we don’t realize is that by relying on these self-serving, primitive instincts we are quite literally shutting down our capacity to see and generate novel solutions.

“The future of marketing and branding depends on our capability to shift from this competitive mindset to a creative mindset. We need to live in the conscious presence of the frontal lobe, the part of the mind that doesn’t fear that the other guy will steal our slice of the market share pie but envisions a way to make a bigger pie. By quieting the selfish impulses of the body, you’ll begin to evolve and engage the mind that is “no body” and “beyond self” and you will create bigger and better outcomes for everyone.”

And that’s just the kind of social evolution so many people are looking for these days or, at least, reacting negatively to the absence thereof. Van Praet bases his book on the old adage that we can, and should, do well by doing good. And it’s nice to see so much evidence that it works.

As I was reading Unconscious Branding and working on this review, I was deep into writing and developing a workshop on “personal branding” for nursing students about to enter the workforce. The challenge I was facing was how to coach someone to communicate who they are and what they stand for in a fulfilling and authentic way. So much of the personal branding conversation is about externals: dressing right, coming up with some snappy things to say in an interview or on your Facebook page (“I’m a people person!”) or otherwise trying to package yourself as someone you are not. My approach is different: work on the internal self by understanding how using neuroscience can make you both a better, more balanced individual and help others to see you that way, as well.

Given what I was working on, Van Praet’s book turned out to be a gold mine of studies and data. And what’s clear to me is this: every single one of his points on connecting consumers to your brand is also useful for connecting your employees and your company culture to your brand. Because great brands don’t come from great products, they come from great companies.

You may not have realized that consciously, but I bet you already knew it in your unconscious mind.