I subscribe to the Sunday New York Times so I can access the New York Times on line. I subscribe to Andrew Sullivan’s Dish blog and to Rhapsody’s music library. I subscribe to Netflix, too. I pay money for those services. But beyond that, almost everything else I do on line — and probably everything you do — is free. We know have a huge economy on line that produces almost nothing that shows up in our calculation of the Gross Domestic Product. Does that mean it’s worthless? No. Does it mean that it really adds nothing to our economy? It’s hard to tell.

James Surowieki deals with this question in a great article in this week’s New Yorker.

Our main yardstick for the health of the economy is G.D.P. growth, a concept devised in the nineteen-thirties by the economist Simon Kuznets. If it’s rising briskly, we know that the economy is doing well. If not, we know it’s time to worry. The basic assumption is simple: the more stuff we’re producing for sale, the better off we are. In the industrial age, this was a reasonable assumption, but in the digital economy that picture gets a lot fuzzier, since so much of what’s being produced is available free. You may think that Wikipedia, Twitter, Snapchat, Google Maps, and so on are valuable. But, as far as G.D.P. is concerned, they barely exist. The M.I.T. economist Erik Brynjolfsson points out that, according to government statistics, the “information sector” of the economy—which includes publishing, software, data services, and telecom—has barely grown since the late eighties, even though we’ve seen an explosion in the amount of information and data that individuals and businesses consume. “That just feels totally wrong,” he told me.

We’re getting so many things free that it’s distorting the way we value the economy. But those free things — like Twitter, like free website design software, like Google or Apple maps — add a great deal of value to those who use them, saving us money we spend elsewhere. Brynjolfsson says that when we underestimate the value of the free parts of the economy, we distort our view of the economy as a whole. When a free service — like the maps and navigation apps on our smartphones — becomes ubuiquitous, it can kill off existing companies, like Garmin. So, while it looks like a formerly great company has lost a huge amoung of value, that doesn’t mean the overall economy has lost value. In fact, it’s become more valuable. The problem is, when new technologies in the past have driven out old technologies, they would enter the revenue stream of the economy and boost G.D.P. But that’s not happening this time. And the value we’re not accounting for may be worth hundreds of billions of dollars a year.

The enormous gains for consumers in the digital age often come at the expense of workers. Wikipedia is great for readers. It’s awful for the people who make encyclopedias. Although the digital economy creates new ways to make money, digitization doesn’t require a lot of workers: you can come up with an idea, write a piece of software, and distribute it to hundreds of millions of people with ease. That’s fundamentally different from physical products, which require much more labor to produce and distribute. And while digitization has already transformed the media and entertainment businesses, it’s not going to stop there. “There are very few industries that are going to be unaffected,” Brynjolfsson told me. The value that the digital economy is creating is real. But so is the havoc.

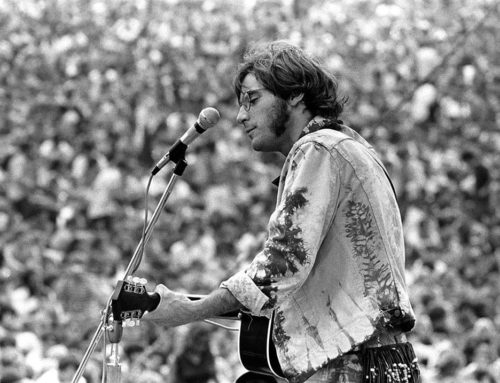

(Picture: The Nav System screen on the new Tesla S. Source: Motortrend)