(The concluding segment of Branded to the Bone, Part 1. To start at the beginning, click HERE.)

If only all we needed was purpose, what a sweet world this would be. But there’s a reason there are four more parts to this book. Purpose alone is not enough.

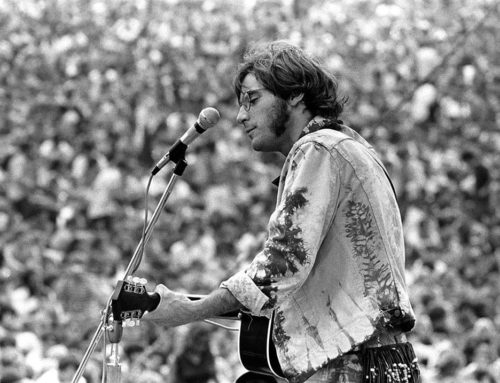

When I was 23 years old, I opened a restaurant at 22 All Saints Road in London, on a small street near Portobello Road. At the time, the neighborhood was London’s version of Greenwich Village or Haight Ashbury. Island Records was around the corner and musicians and entertainers roamed the streets. These a hard, grimy part of town with nightly street fights, runaways and shady deals galore.

The restaurant, quaintly named Guru Nanak’s Conscious Cookery was my first ever adventure in to the world of business and it had massive massive clarity of purpose: to make the world healthier and happier through bountiful organic foods and yoga. The concept was modeled after similar restaurants in California—particularly The Source on Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles—and featured fresh produce specially grown for us and delivered from the countryside each morning.

The restaurant, quaintly named Guru Nanak’s Conscious Cookery was my first ever adventure in to the world of business and it had massive massive clarity of purpose: to make the world healthier and happier through bountiful organic foods and yoga. The concept was modeled after similar restaurants in California—particularly The Source on Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles—and featured fresh produce specially grown for us and delivered from the countryside each morning.

The cuisine could best be described as “exuberant.” Sandwiches where three to four inches thick and layered with flavors. Salads exploded vertically off the plate, vibrant with color and richness. Indian flavors infused rice dishes. Pasta dishes were sinfully rich. And the desserts! Our cheesecakes and pies were irresistible.

That first summer, within weeks of our opening, we were packed. Movie stars and writers, singers and rock stars. Alan Bates had a regular table by the front window. Lulu frequently came in with friends You’d see Allen Ginsberg in one corner and Wilt Chamberlain in another. Special effects artists from Dr. Who show and other local artists. The emerging gay pride movement marched in one night in drag, all carrying party balloons (talk about exuberant!) and cleaned us out of desserts and then continued coming week after week.

That first summer was a total success. Then came the second summer, which was problematic. There was no third summer.

Because purpose was not enough.

So what went wrong? First of all, I got bored. I loved cooking and inventing interesting dishes. But not enough to spend 18 hours, six days a week at it. So I delegated more of the work to others and spent less time in the restaurant. And I was exhausted. Nine out of ten restaurants fail because no one tells you how hard it is. Or they tell you and you don’t listen. Eighteen months is the average life expectancy of a new restaurant, even when they’re started by pros. When they’re started by enthusiasts, it’s amazing when they last a month.

Second, we had people problems. Most of the “employees” were volunteers from the yoga classes upstairs. They were good kids but most had only the vaguest concept of how to work. One young woman in particular was a problem. If you sent her down to the market to buy something we were suddenly out of, she might come back and she might not. When she went out the side door, she never thought to close it behind her. And this in a neighborhood rife with snatch-and-grab crimes. Once, when she was cutting onions in a fog of meditative ecstasy, she dropped the knife and, because she was wearing sandals instead of shoes, the knife impaled itself in her instep. I still remember standing there looking at that knife, as it twanged back and forth, and realizing that there really wasn’t a single job in the restaurant I could trust her to do.

Suppliers were problematic, too. Small organic farmers growing custom fruits and vegetables for restaurants worked well in sunny California, where Alice Waters at Chez Panisse could find real pros. But in London it was different. These were eccentrics who thought it would be fun to move to the country and be organic farmers but who found the pressures of pre-dawn delivery routes NS the expectations of clients to be somewhat stressful. One of them stood in the kitchen one morning and screamed at us for serving tomatoes to our customers, which everyone knew were pure poison and only one step removed from the deadly nightshade. Another refused to sell us his produce when he discovered we were cooking in aluminum pots, which were all we could afford.

Third, we had no processes. Or at least not the right ones. Yes, we knew how to cook and we knew how to entertain customers. But we didn’t know how to run a restaurant. And certainly not a business. So bills piled up and cash flow was spent on the wrong things and our ability to withstand setbacks declined. And so one day, when our 18 months of fame were over, we closed the doors. We had purpose and we had product. But without a balance of people and process, we never got to payoff.

But it’s not only bright-eyed optimists for whom purpose is not enough. As we saw, both Apple and Blockbuster had their problems with purpose (Apple worked it out, Blockbuster didn’t). Proctor & Gamble, widely known as a great company with lots of intentional focus on defining purpose for each brand and business unit, has recently passed through a troubling time under former CEO Bob McDonald, a veteran executive of the company and a champion of purpose. Already armed with a strong sense of purpose and brand integrity, Proctor & Gamble under McDonald upped the ante on purpose And yet the results didn’t follow and McDonald’s tenure lasted only four years. Purpose alone is not enough.

That doesn’t mean that P&G will abandon purpose in the years to come. In his book, It’s Not What You Sell, It’s What You Stand For, purpose guru Roy Spence details and in-depth market study of more than thirty thousand brands that P&G conducted. What they found when they looked at the top-performing twenty five brands, they found that all of them were focused on what Spence calls “higher-order” purpose.

“P&G believes so deeply in the idea of purpose,” Spence writes, “and its ability to drive performance that it has recently codified everything the company has learned about purpose in an internal manual.” Spence has managed purpose for clients through the Austin, Texas, ad agency, GSD&M. They developed a concept they called “purpose-based marketing” and used it to transform the business of companies as diverse as Southwest Airlines, WalMart, Whole Foods and P&G.

“Why does purpose matter?” Spence asks. “Why not just work on sound strategy and positioning year after year and have a good, viable business in the marketplace? You can certainly do that and you may even have reasonable success doing it. But in our experience, purpose offers up a host of benefits, including easier decision making, deeper employee and customer engagement, and ultimately, more personal fulfillment and happiness.”

And that’s true in study after study, Jim Collins in Built to Last to Raj Sisodia, Jag Sheth and David Wolfe in Firms of Endearment, we see that, over time and with everything else in balance, companies that are Branded to the Bone will dramatically outperform the market and their competitive set.

Investing to make money? Or to make the world a better place? It’s not an either or question any more. It’s a question of integrity of purpose.

The final thing to say about purpose is this: companies don’t have purpose, people do. The combined sense of purpose of the people who make up a company—from top to bottom—is what defines and delivers on the purpose of the brand.

It all comes down to people.