(C’est incroyable, mais hier j’étais drôle en français.)

I started studying French in 7th Grade, or maybe it was 6th. It’s hard to tell because it was the year my parents moved us to Australia and enrolled me in The Peninsula School, a few miles south of the last train stop in Frankston, outside of Melbourne. When I left California it was summer and when we arrived in Melbourne it was winter and the middle of the school year. So I was put in a class with the other 12-year olds. The terminology of naming classes (or “forms”) was so untranslatable to the American system, that I never figured out what grade I was in. And besides, I had tougher things to figure out. Like French.

Frankston, where we lived, was a tough beach town where, just a year before, Gregory Peck and Ava Gardner had come to film a Stanley Kramer movie about a post-nuclear war world called On The Beach. If you can find the film, you can see footage of Peck coming out of the train station and striding along the parade of shops across the street, playing the part of the American submarine captain who had found Melbourne and Port Phillip Bay as the last remaining outpost of human life, where everyone was counting the days until the slow-moving belt of radioactive fallout reached that far south and put the last lights out.

The beach of the title has a double meaning. It refers to the little beach that was down the cliff at the end of our street, where the Mount Eliza Sailing Club was located and where, in the movie, Peck and Taylor begin their love affair. But it also refers to the old Navy term for a captain who no longer has a command: he’s on the beach. Peck still had a nuclear submarine, but who cared anymore? There was no place to go but where they were.

The movie is memorable for the portrayal of people waiting to die and trying to cheat death with danger. Dangerous drinking, dangerous liaisons and dangerous driving. The hardest part of the film to watch, at least for me, is the part when everyone goes out to the Phillip Island racetrack and proceeds to destroy a collection of Jaguars, Mercedes and other highly collectable sports cars that today would be worth a fortune. As I remember, Fred Astaire, in particular, does unspeakable things to a bathtub Porsche. It’s hard to take.

So was French. In those days, in what was essentially a British prep school, the teaching of French was presented as a kind of intensive Chinese water torture designed to destroy normal brain function. It was taught as a succession of impossible tasks which, if you succeeded in each of them, would earn you great social distinction but leave you tongue-tied and bug-eyed in response to anyone who asked you a question in that language.

First, as I remember, we were given the six or seven verbs in French which followed the rules. These were called “regular verbs” or “verbes réguliers.” That everything in French was backwards was an early warning sign. Next, you had to memorize the “irregular verbs.” In French, there are a myriad of those, myriad being the Greek word for a number greater than 10,000. Beyond which, who’s counting?

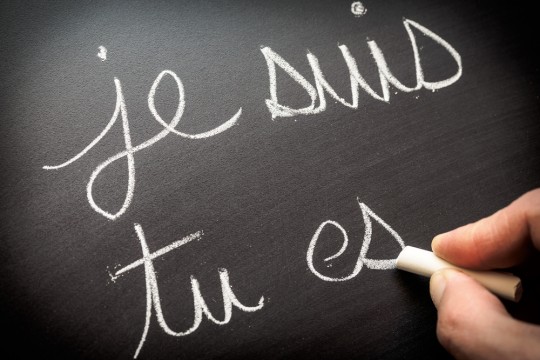

Learning those verbs – or more or less not learning them – consisted of chanting them out loud as a group. “Je suis, tu es, il est, nous sommes, vous avez …” No, wait, “avez” is a whole other stream of misery. “J’ai, tu as, il a, nous avons, vous avez, ils ont.”

“Ont?” Where did that come from?

Given that we had only an hour of French a day, the complete futility of the project seemed as likely as putting a man on the Moon, which the television announced our President Kennedy said America was going to do and which the headmaster of my school, the Hon. Dudley Barrington Clark, said would never happen. He said it with a knowing smirk.

Learning cricket was easier than French. If the ball comes to you, throw it back to someone. Learning Australian Rules Football was harder. Aussie Rules resembles polo without horses and is based around a philosophical conundrum I could never understand called, “Offsides.” What does offsides mean? I have no idea, it was all French to me.

Once it was clear we would never actually internalize French’s verbal irregularities, they made us memorize French nouns, adverbs and adjectives. I later learned there are some easy rules to help with all that but no one ever told us about those devices, or maybe they hadn’t figured them out yet. Because here’s the glorious secret of French I never realized until many, many years later: French is easy.

About 70% of English words are actually French. So if you speak English, you’re almost three-quarters of the way there. All you need to know are a handful of easy rules. And +/- 105 irregular verbs.

Here’s a rule: if a noun ends in –ion, it’s probably the same word in French. Just pronounce it like Charles Boyer overacting and you’re at your destination (des-tin-a-SHE-own).

Here’s another rule: if a word ends in -e, you don’t pronounce the e, you end on the consonant before it (except in 423 specific cases which you’ll have to memorize). If it doesn’t end in –e, you’re screwed. You now have a word you can begin but not finish. You say the first part of it and then let the rest hang in the air, kind of like you someone punched you in the throat.

Years later, I found out there’s a simple mnemonic device to help you remember which consonants you can end a word with: it’s careful. If a word ends in c, r, f or l, you’re good to go. How come no one ever told us that? Honestly, I don’t think they’d gone that far themselves. Not even the French knew that one.

We eventually returned to California, where the little I’d finally learned about Aussie Rules simply emphasized the irrelevance of my teenage self. I studied French through high-school and into college and, in time, enough of the words lodged in my head that I began to be able to form some of them into sentences, like “J’ai une rhume incroyable” which means, “I have a room in Croyden.”

When I was 19, I decided to drop out of school and go to Oslo to get a job doing something that didn’t require me to memorize anything, which is how I ended up drinking Stella Artois in a bar in Brussels and hitch-hiking to Paris. That’s where I learned I’d spent seven years studying a type of French that no one in France understood. Whenever I opened my mouth, I was ruled offsides.

Here’s how I finally learned to speak French: I hitchhiked to Morocco. In Morocco, a former French colony, lots of normal people speak French as a second language, which means they pronounce individual words in a logical sequence, unlike Parisians, who speak like someone pressed their fast forward button four times.

One night, I was sitting in a roomful of charming bohemian acquaintances somewhere off the Djem-El-Nah in the old quarter of Marrakesh when someone handed me a little pill.

“What’s that?”

“Dexedrine.”

“Oh, OK.”

When you take a Dex tablet, lots of fun things happen. You can drive an 18-wheeler all the way from Amarillo to Santa Monica without a stopping. You can leap up and do a thousand jumping jacks. Or you can do what I did, which is you can start talking.

When I started talking, there were about 15 people in the room. Some hours later, I noticed I had cleared the room. So, still talking,I went downstairs and hit the streets. And since no one I could find spoke English, I started speaking French.

I talked to the street kids and the shopkeepers. I ran in to a man I’d bought a vest from and stayed up all night with him and his brother, holding court in my fascinating way, all in French. I don’t know if they understood a word I said, but I did. And that’s what counted. Released from my normal inhibitions, I was talking the talk. Or however you say that in French.

Over the years, I returned to France many times. If I was there long enough, I would sometimes dream in French. But there was still a troubling problem: I was good at blurting out a few charming pleasantries and maybe a question in French, with an accent that was good enough to pass. But when the person I was talking to started to answer, I had no idea (aucune idée) what they were saying. Rien, zip, nada. I was simply lost.

So that brings me to yesterday, the day I made people laugh in French. I was in Montreal getting ready to speak at a conference at Concordia University and asked a woman in the Communications department if she could help me with something in French. I wanted to start my talk in French as a courtesy to my hosts and thought if I said something self-deprecating, it would be a nice way to start.

I told her what I wanted to say, in French, and she looked at me with a kind of astonished look on her face.

“No good?”

“No, that was really good. I’m surprised.” She said my accent was good, too. “When Americans speak French, they have such sweet accents.”

Which is not, I’m told, something you can say for some French-Canadians. After I returned to Paris from Marrakech, I palled around with a couple of guys from Quebec. When they spoke French, I had to translate what they said for the Parisians who were trying, not very hard, to understand them.

When I got up in front of the conference to speak, I dove into my French introduction.

“Allez, on-y-va,” I started off, calling the room to attention. “Je suis heureux de vous voir. Je m’appelle Dain Dunston, je suis écrivain et entraîneur exécutif. Je voudrais vous parler en français, mais il y a un probleme … moi, je parle français assez bien pour commencer un conversation mais pas assez bien pour le terminer.”

Then I translated. “For the rest of you,” I said, “I just explained that after years of intensive study, I speak French well enough to get into a conversation … but not well enough to get out of one. “

The punchline got the laugh I expected and it was only when I was in the car to the airport did it sink in that when I said it in French, it got the same laugh in the same place, and just as strong. To my amazement, I had been funny in French which, if you’ve ever heard a French joke, is not that easy. And when those people laughed, there was no misunderstanding what they were telling me: they got what I was trying to say.